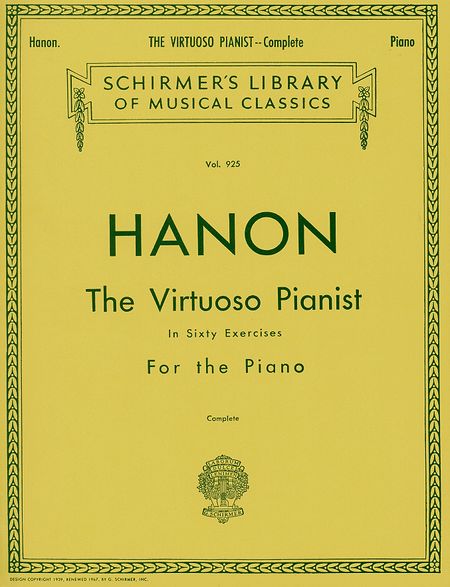

A few days ago, I chanced upon my old, shiny, red

Hanon

book

(online version). I remember my teacher assigning a couple of them to me but I never

understood the underlying principle of these exercises. After much

research around piano forums, I've realized that many pianists consider

the Hanon exercises as antiquated, unmusical, obsolete, a waste of time

and worse, injurious to one's hands

(click here for more info). I immediately dropped these

exercises but saved the scales and arpeggios.

Now, as a

mature pianist and having learned much over time, I leafed through the

Hanon book once again with critical eyes. Indeed, repetition of

predictable patterns is the key concept of the Hanon exercises. It's

just full of short and long repetitive figurations (trills, tremolos,

repeated notes) written in many permutations (but mostly in the key of

C).

The principle is the same as physically training an athlete

or working out in the gym. By doing repetitive drills, one's speed, stamina, and strength improve over a period of

time.

After

reviewing all of the exercises, I've arrived at the following

conclusions: 1) about 80% of the exercises are indeed a waste of time,

2) most of them seem to be illogically ordered; but 3) about 20% have

real applications in classical pieces.

I have picked 10

of the most useful ones, to be studied in the following order (please

see end of list for my practice suggestions):

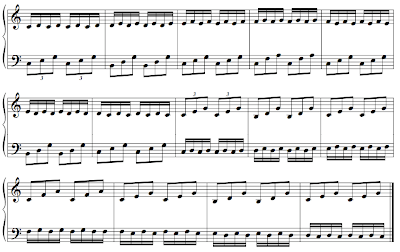

1. #46 - The Trill

Virtually

all major composers (Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, et al) used trills

in their compositions. When properly executed, the trill mimics a bird

call or even a vocal vibrato. When combined with the right dynamics

and tempo, it has a penetrating effect on the listener.Technically,

the trill is one of those best-kept secrets in improving overall speed

and dexterity.

For this exercise, it is best to master them hands

separate (HS). The trill of outer fingers (5-4-3) cannot simply compete

with the trill of the inner fingers (1-2). On their own, they can

achieve a degree of speed not possible when played hands together (HT).

Play close attention to the following fingers: 5-4 and 4-3. Never trill

them too much as to strain them.

For beginners: The

exercise looks menacing and may be overwhelming for newbies. I suggest

you reduce the exercise as follows: eliminate the extra trills on the

3rd and 4th beats (i.e, just do 2/4 instead of 4/4 time). Work the first

6 measures only.

For variety: You could try the exercise one

octave lower. The hammers in the lower register are heavier, thus you

will encounter more resistance. It's exactly like working out on an

elliptical stepper. Once you're comfortable with a certain resistance,

you increase it a bit. You can also transpose this exercise in

practically any key if you get bored playing just white keys. Try in the

key of A and E.

2. #44 - Repeated Notes

There

are plentiful repeated notes in the music of Bach, Beethoven, Prokofiev

and other composers, often representing a drum or some percussion

instrument figuration. In some of Scarlatti's keyboard sonatas, they

mimic the strumming of a Spanish guitar or mandolin. A newbie is often tempted to

use only one finger for the repeated notes when different fingerings are

clearly written for each note. This simplification often results in the

loss of "color" of the repeated notes and a build up of tension on the

poor finger that plays everything.

For beginner: This

exercise is also best practiced HS and if needed, reduced to 2/4 from

4/4 (eliminate third and fourth beats). The first four measures are a

good warm up but once mastered, the student may simply skip this and

start on the fifth measure up all the way to the last measure of the

page. No need to do the repeat.

For the more experienced: After mastering the first four measures, skip to the second page. No need to do the repeat.

For the advanced: You may replace this exercise with #47. The repeat is unnecessary.

3. #6 - Basic Extension

There

is big stretch from the first note to the second note of every

measure--a sixth in fact. The real interesting thing are the inner notes

that descend from a fixed upper note (played by the 5th on RH and 1st

on the LH) in every measure. The descending notes are played by 4-3-2 on

the RH 2-3-4 on the LH, as if a mirror image. This figuration is very

common in Baroque and Classical period pieces (just look at some of the

preludes of Bach, sonatinas of Clementi, variations of Beethoven,

etc.).

If this exercise can already be played

perfectly, the pianist may replace this with #31. This time, the stretch

is an octave span. This should be very effective in preparing the hands

for octave studies.

4. #40 - Chromatic Scale

The

chromatic scale is one of those enthralling effects in classical music.

In Beethoven's Fur Elise, there is the ever famous descending chromatic

scale after the climax. Without a good grasp of chromatic scales, it is

hard to interpret the music of Chopin, Beethoven, Liszt and so many

others who exploited chromaticism in their music.

The

chromatic scale is actually easier to learn than the major and minor

scales because the thumb, wrist, and arm movements are simpler. In some

ways, it's a good preparation for the study of scales. Most chromatic

scales are played "leggiero" or light. To do this, practice each note staccato

in slow speed. As you increase speed, make the staccato lighter. This

should produce a "feather-like" articulation.

For beginners: Study "At an octave" and "In contrary motion, beginning on the octave".

For the advanced: Add "At a minor sixth" and "In contrary motion, beginning on the major third".

5. #38 - Running notes

Every

pianist must eventually deal with rapid running notes. It's just part

of the trade. This exercise offers a fair introduction to the role of the thumb in facilitating the execution of running notes.

There are two schools of thought regarding the use of the thumb:

Thumb Under and Thumb Over.

I won't go into detail regarding the merits and demerits of each but

suffice it to say that from Hanon's thumb turning exercises (#32 to

#36), one could deduce that he advocated the Thumb Under method.

Whichever is most effective depends on the situation.

For the advanced: Play this C scale in interval of 10, i.e, the LH plays as is while the RH is raised a third up:

RH: e-f-g-a-b-c-d-e

LH: c-d-e-f-g-a-b-c

The fingering is also modified (numbers in bold are where the thumbs do their hard work):

RH: 3-1-2-3-4-1-2-3

LH: 1-4-3-2-1-3-2-1

6. #15 - Broken Thirds

Hanon

is spot on with this exercise. Thirds (double or broken) is just

everywhere in classical music and are one of the most difficult to

execute convincingly. When played well, they sometimes mimic laughter or

two persons singing together (tight counterpoint). It is said that Mozart conceded that his

rival Muzeo Clementi played thirds better than him. Fast scales in thirds are so treacherous that some virtuosos cheat

on the notorious D scale in thirds in the Brahms second piano concerto.

For the advanced: Add #50 (legato thirds) and #52 (scales in thirds).

7. #20 - Little Arpeggios

This exercise runs through the arpeggios (broken chords) in the second inversion based on the C scale. These chords are the C major, d minor, e minor, F major, G major, A minor, and b diminished. The general awkwardness in the LH fingering (5-4-2-1) and RH (1-2-4-5) in playing the first beat of every measure is the main reason why this exercise has to be mastered.

As preparation, play each first beat as a block chord until the grasp of the chords becomes very comfortable.

8. #53 - Octaves

Some of the most memorable moments in piano music are the big, thundering octave passages, such as in the concertos of Tchaikovsky, Liszt, Saint Saens, and others. Pianists work on their octave technique for hours on end to achieve the desired effect. This exercise is a good stepping stone.

Start wtih chromatic scale in octave which is actually the last part of the exercise. Go through it slowly and try to bring out the outer notes, i.e., those being played by the 5th finger of either hands. When sufficiently mastered, start with the second page of this exercise.

9. #39 - All scales

10. #41 - All arpeggios

Perhaps the most important among all the exercises in the Hanon book are the scales (#39) and arpeggios (#41). So important are they that most conservatories and collegiate music schools require the prospective students to play them during auditions and with good reason. All the most essential technique are codified in the scales and arpeggios and together with octaves, thirds, and sixths, they make up for 80% of the technical difficulty in written music.

I will write a separate blog detailing my suggestions on practising scales and arpeggios.

When to take up the Hanon exercises: It makes sense to introduce the Hanon exercises after the third grade of the John Thompson method book or its equivalent. The student should concentrate on mastering the first eight exercises in the above list. To his/her delight, he/she may discover that the exercises will have prepared him/her well to study Beethoven's Fur Elise, Clementi's Sonatinas, and other intermediate level pieces.

How

to practice Hanon: Make sure you practice this hands separate (HS) first,

gradually speeding up without sacrificing note clarity and evenness.

Keep the wrist relaxed to avoid strain. When either

hands are sufficiently warmed up, play them hands together (HT) but

choose a speed that both hands can handle. This is normally slower than

either hands could achieve separately.

For

the more experienced: Instead of playing the exercises mechanically,

you may shape them through dynamics. Begin

softly (p) on the first measure, gradually do a crescendo, reaching a

mezzopiano (mp) after a few measures, then attaining an mezzoforte

(mf), then a forte (f) on the first descending measure. From here on, do

the exact opposite, i.e., a diminuendo, falling back to piano (p) on

the last measure. Also, try doing an allargando as you reach the high

point of the exercise, then resume "a tempo" until the last measure

where you may do a slargando.

For the more advanced:

Instead of a uniform crescendo from the first measure to the middle of

the piece, you can do a mini crescendo-diminuendo in every measure,

corresponding to the rise and fall of the notes within that measure. As

you move to the next measure, you begin with a volume slightly higher

than the first note of the previous measure, then proceed to do a

crescendo-dimuendo. The effect is like the rising and falling of waves.

On reaching the descending measure, apply the opposite dynamic, i.e.,

diminuendo-crescendo. Maintain a steady tempo all throughout. I would highly recommend using a METRONOME to reign in the tempo.